Regarding the Face of God: On the Paintings, Drawings, and Notebooks of Paul Thek

Wallace LudelIssue 11

Criticism

Between 1963, when the artist Paul Thek began his fleshy, uncanny “Meat Pieces”—sculptures that are hyperreal bisected morsels of human anatomy, though they’re typically ambiguous as to what part of the body they represent—and 1967, when he left for Europe, Thek didn’t make a single painting and produced only a few drawings. In 1969, he wrote Eva Hesse from abroad, “[I] have started painting again, after five years. It feels really fine. The whole fall season seems to have been beautifully psychic, the same inner things happening to many people far apart. I think now perhaps we’re all part of one big creature, like coral, separate consciousnesses, parts of a great big one. Just a theory so far.”

Untitled (oval landscape) ca. 1970 watercolor and colored pencil on paper 7 x 91⁄2 in/18 x 24 cm Photo: Joerg Lohse ©Estate of George Paul Thek, Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Though it’s his sculptures and installations that have come to define the greater part of his legacy, it’s Thek’s paintings, drawings, and notebooks that I fall again and again in love with. His retrospective “Diver” began at the Whitney in 2010 before traveling to Los Angeles’ Hammer Museum in the summer of 2011, the same summer I turned 20 and the last one I spent in LA. This was the first time I saw Thek’s work en masse, walking through The Hammer with my father. I had spent the previous summer working there, at The Hammer, and my father had spent it having, then recovering from, open-heart surgery.

Untitled (self-portrait, tomato, hippo) ca. 1970 pencil on paper 14 1/8 x 19 in/36 x 48.5 cm Photo: Joerg Lohse ©Estate of George Paul Thek, Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Thek, though certainly a realist, was a man of faith, and a religious charge always felt present to me in his paintings and drawings. I encounter them the way one might walk through church after church in Europe, feeling the vibrations from so many years of worship within their walls, the weight of history with each new crucifixion scene. Coinciding with this religiosity is the omnipresence of contradiction. Thek identified as a “predominately-gay” Catholic man, struggling between the grounding of his devotion to reason and philosophy and his synchronous consecrations of divinity, all wrapped up in his unmoored on-again-off-again expat lifestyle.

In a telegram to friend and artist Ann Wilson, he wrote, “I seem to teeter on the brink of enlightenment, yet my energies are sapped at the root by my awareness of serving two masters, with its traditional results, alienation from everything.”

HIS INTEREST IN CHILDLIKE RENDERING GREW IN ACCORDANCE WITH HIS PROXIMITY TO DEATH.

In 1969, he began painting on newspaper, a practice he would maintain for the rest of his life. The decision to paint on a non-archival surface can be read many ways, though it’s no doubt inherently anti-market (and a nightmare for conservators). At once pop in their everyday-ness and anti-pop in their rough, unfinished qualities, the paintings are often rudimentary and frenetic. While most of the newspaper is gessoed over, its edges are often left raw so that words, dates, and phrases are partially intelligible. For Thek, a remarkably skilled draftsman, to suddenly choose to paint so crudely felt like a leap towards the internal—shifting his values towards brevity and the poetic. This intentional reversion always struck me as something to carefully consider and, looking back at his body of work in those final decades, his interest in childlike rendering grew in accordance with his proximity to death.

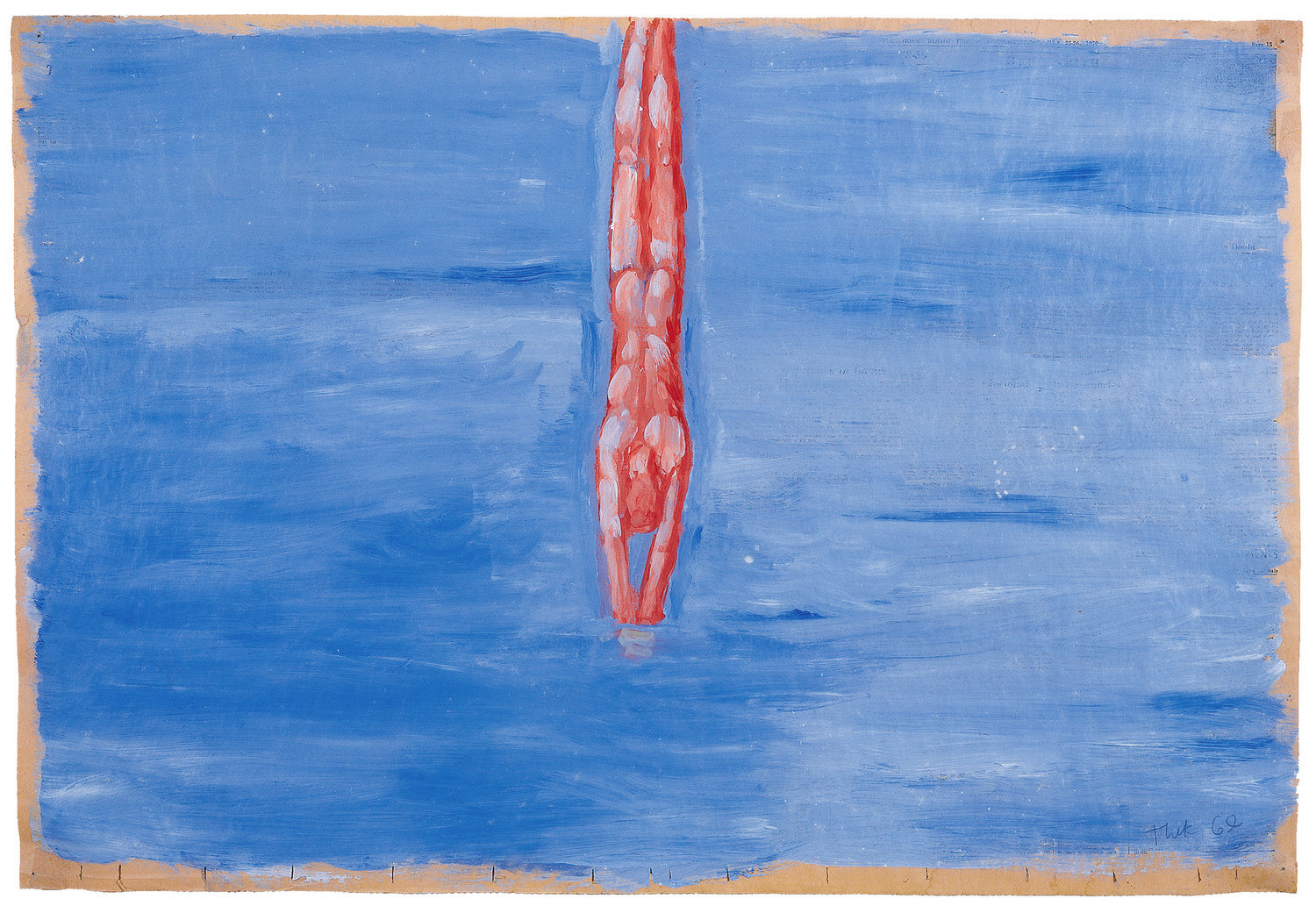

Untitled (diver), 1969. Synthetic polymer on newspaper, 26 1/8 x 36 1⁄4 in. (66.4 x 92.1 cm). Kolodny Family Collection Photo: Orcutt & Van Der Putten ©Estate of George Paul Thek

Once again mirroring religious spaces, allegory is everywhere in the paintings. The “Diver” paintings, 1969–70, from which his posthumous retrospective took its title, are two images of a nude male mid-dive into water. These paintings are speculated to have been inspired by an ancient fresco referred to as the Tomb of the Diver, which was unearthed in Paestum, Italy a year prior. (Thek was living in Rome at the time of its discovery and could have easily seen it in the newspaper.) The fresco depicts a nude man in profile, diving from a board into what’s presumed to be the afterlife; a mostly empty composition save for the figure, two bare trees, the diving board, and hints of a body of water. In both of Thek’s “Diver” paintings, the figures’ feet are above the frame and so we believe him to be mid-submergence. His body is red and painted with blue and white gestures that define his muscles. Cloudy-white pokes through the blue field and what’s assumed to be water could just as easily be sky. At once ebullient and lonesome, womb-like and deathly, these paintings present the same contradictions as Thek himself.

IMAGINE HAVING TO BURY YOURSELF OVER AND OVER.

In 1970, he began keeping a daily journal. It was these notebooks in particular that I remember laboring over at the museum—they were shown in vitrines, splayed and abreast like pinned butterflies or religious artifacts. It was an art-encounter unlike any other I’d had at that age and there I was, studying them with my father who had so recently evaded death and whose chest had been opened and displayed in a similar manner—though his had since been sewn shut; a long, narrow scar blossoming down his sternum. The notebooks reveal a man full of contradiction, at once brilliant and plagued by self-doubt, profoundly intelligent and deeply childlike. Some pages are deftly finished drawings and watercolors—stunning self-portraits, still-lives, and landscapes of places like the Italian island of Ponza, which Thek frequented. Other pages are more meandering and diaristic; a multiple-page spread is composed of many banners that all read, “get over yourself!” The notebooks contain long-passages of spiritual texts copied word-for-word as well as his own quasi-devotional musings. The repeating sentence “I shall have a sense of humor at all possible times” spans entire pages, like a religious chant or perhaps a reprimanded child repeating a phrase at a blackboard (á la Bart Simpson). A list titled “96 Sacraments” enumerates 96 activities, “to breathe . . . to pee . . . to do the dishes . . . to forget bad things” and so on, each of which is numbered and followed by “Praise the lord.”

Page from Thek’s notebook #75, c. 1975. Watermill Center Collection; courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York ©Estate of George Paul Thek, Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Upon returning to New York in the late 70’s after just under a decade in Europe, despite his myriad successes abroad and what would many-years posthumously be regarded as historically significant museum and gallery shows, Thek found himself in a New York that seemed to have forgotten about him entirely. His work was unfashionable and the market didn’t take kindly to it. He developed an anti-institution ethos and shunned some of the few opportunities that presented themselves to him. In 1984, preparing for a show at Barbara Gladstone Gallery, he puzzlingly turned away the trucks that had come to collect his work. In 1981 he refused to retrieve his most famous work, “The Tomb,” (an installation that included a life-cast of Thek laid to rest) from its latest exhibition and so it was destroyed, when asked why, he answered, “Imagine having to bury yourself over and over.” After teaching a Four-Dimensional Design course at Cooper Union from 1978–79 and again from 1980–81, Thek found himself bagging groceries and working as a hospital custodian, among other odd jobs.

In the late 80s, as he grew erratic and reclusive, watching friends and partners die of AIDS and slowly isolating himself from those who were still well, in addition to growing more crudely rendered, his paintings furthered their dark and quizzical elements. Yellow text on a violet background reads, “Afflict the comfortable, COMFORT THE AFFLICTED” (1985). Violet text on a yellow background reads only “SUSAN LECTURING ON NEITZSCHE” (1987). Susan here is, as you may have suspected, Sontag, who dedicated her 1966 book, Against Interpretation, to Thek, then dedicated her 1989 book, AIDS and Its Metaphors, to his memory. Sontag and Thek’s relationship was significant and unique to say the least—she was a friend, a mentor at times, at one point they seriously considered having a child together, and, growing isolated in his final years, Thek wrote many letters to her to which she refused to respond. In the end, she delivered the eulogy at his funeral.

Susan Lecturing of Nietzsche, 1987. Synthetic polymer on canvas board, 13 x 16 15/16 in. (33 x 43 cm). Watermill Center Collection Photo: D. James Dee ©Estate of George Paul Thek, Courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

In 1988, the year of his death by complications due to AIDS, Thek, never having returned to any semblance of financial stability and having grown steadily unwell, mounted what would be the final show of his lifetime in an East Village storefront. The paintings were all done in shades of blue on newspaper and were hung at the eyelevel of a toddler; perhaps knee-height for an adult. He placed a kindergarten chair in front of some of them to drive home the idea that they were for children. (A former colleague of mine, a born-and-bred New Yorker, told me she remembers seeing this show as a small child and was thrilled to find a show hung for viewers her size.) They were worth crouching down to see: One is a small blue color-field with a clock crudely drawn into it and the words “the face of GOD [sic]” scrawled beneath it (1988). Two, both referred to as Untitled (Butterflies), 1988, are renderings of a dozen or two butterflies, done again with a childlike hand; they could be bowties or just pairs of triangles in space. In Dust, 1988, the titular word floats in the middle of a speckled, blue expanse; background and foreground obscuring one another. None of the paintings sold.

A page from Thek’s notebook, 1977:

“you and I and this book

Will soon be DUST,”,

He said,

They said,

We Said,

DEFENSIVE DEPRESSION. [sic]”

The retrospective I saw at The Hammer ended with a full recreation of this final show. I remember walking out of the dimly lit room and into the museum’s courtyard—the wide Southern California sky both making me squint and recalling the blue abyss into which the show’s eponymous diver dove. “Jesus,” my father said, “that was exhausting.”

I found a copy of the long out of print catalog, Paul Thek: Artist’s Artist, at the library. On the very last page is a panorama, the way they used to be done on film, in which the photographer stands in one spot and pivots, photographing on an axis and later collaging the photos together. It’s a photo of Thek on his East Village roof and it’s dated June 1988—two months before his death. He’s sitting at the edge of the roof and looking west; beyond him to his right we see 14th St, the Empire State Building, even the Chrysler building is faintly discernible. He’s wearing a white tank-top and shorts, and despite being this close to death he remains in full possession of his boyish good-looks. The roof is covered in pots and buckets and they are full of hundreds and hundreds of yellow flowers (zinnias? marigolds?). I looked at them, and at him sitting there, and I just started crying. This, to me, encapsulates so much of who he was: A man capable of such extreme paradox, who—knowing he was ill and most likely knowing he was dying—without any money to speak of, goes and buys hundreds and hundreds of yellow flowers and fills his roof with them. Then he sits there, at the edge, and looks out, away from them all, towards the street below.

Wallace Ludel is an artist and writer. His art writing and poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Artforum, BOMB, Narrative, No Tokens, Sporklet, and elsewhere. He recently received his MFA from New York University, where he also taught creative writing.