REVISIT: Kyra Baldwin on THE COMPANY SHE KEEPS

Mary McCarthy wrote The Company She Keeps in 1942. Despite the cover brandishing the words “A Novel,” the professor of the Short Stories class I was taking argued that it was actually a collection and was only labeled a novel for marketing purposes. However, McCarthy was adamant about its classification as a novel, describing it as a “unified story.” Although the six vignettes seem almost purposefully disorienting, they are not linear and they vary between first person, second person, and third person, they all focus on Margaret Sargent. The goal is polygonal: give us as many angles and sides into Margaret so by the end, we understand all of her.

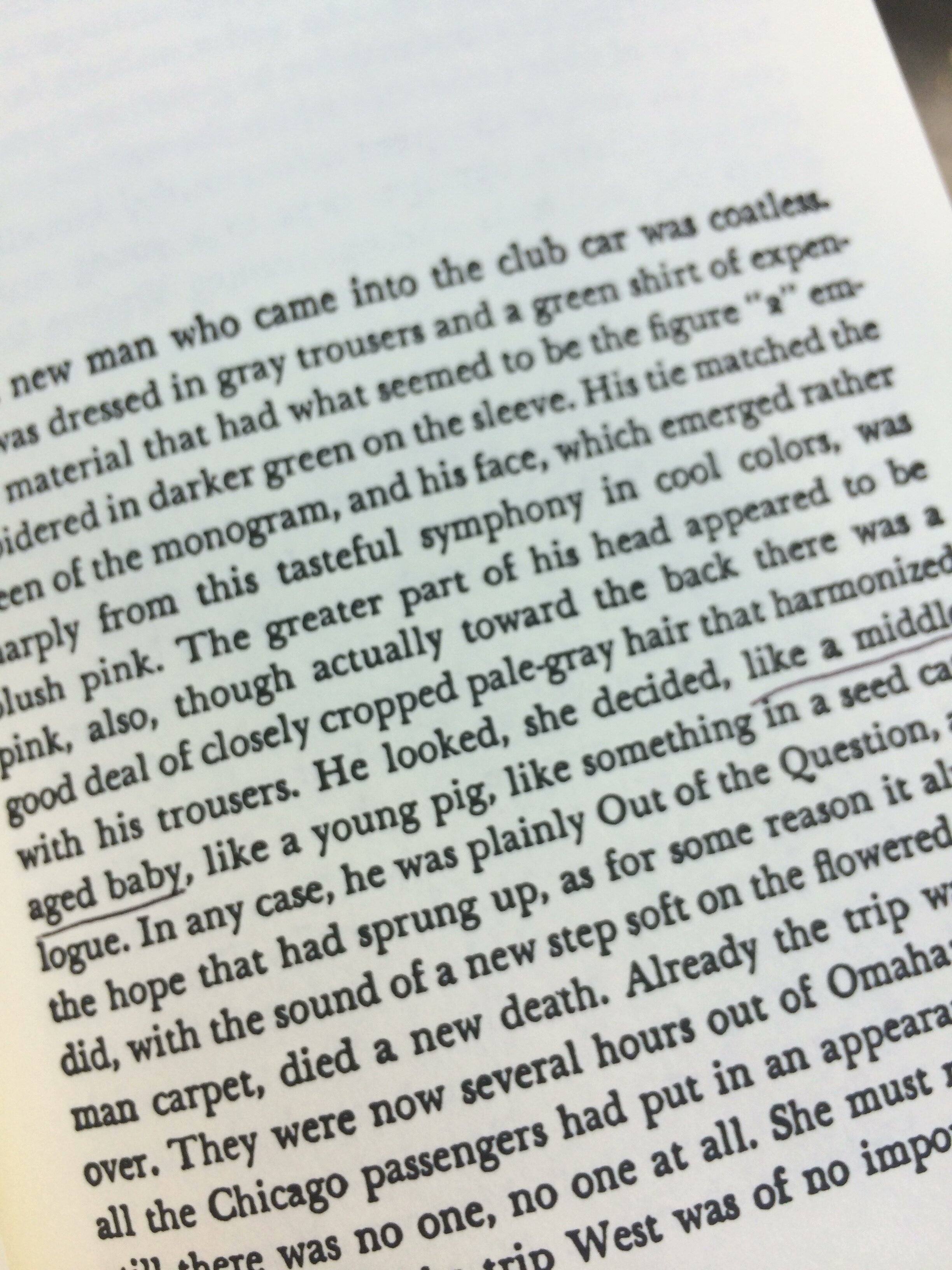

What makes The Company She Keeps so deft and challenging is that Margaret Sargent shares our goal. She also wants to understand herself. In the third chapter “The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt,” she meets a man on a train and despite her initial revulsion, they end up in his compartment. While they talk, Margaret thinks, “Perhaps at last she had found him, the one she was looking for, the one who could tell her what she was really like...If she once knew, she had no doubt that she could behave perfectly; it was merely a question of finding out. How, she thought, can you act upon your feelings if you don’t know what they are?”

The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt

McCarthy portrays Margaret as helplessly confused about her identity. She could be who she was if someone told her how to be who she was. But there are no “palmists or graphologists,” as McCarthy goes on to say, who could ever give a satisfactory enough answer. This is Margaret’s problem. There will never be a Myers Briggs test, an enneagram, a daily horoscope that is thorough or individual or insulting or complimentary enough to ever suffice. Isn’t this, in some way, everyone’s problem?

This question reminds me of another novel I love, How Should A Person Be? by Sheila Heti, published seventy years later. The book begins with its title, “How should a person be? For years and years I asked it of everyone I met. I was always watching to see what they were going to do in any situation, so I could it do too...You can admire anyone for being themselves. It’s hard not to, when everyone’s so good at it. But when you think of them all together like that, how can you choose?”

Both McCarthy’s and Heti’s books define the world through a binary: People who know who they are and people who don’t. The people who don’t know who they are look to those who do for answers, for yardsticks, for proofs. Margaret looks to the older man on the train to explain her to herself, Sheila looks to her friends and fellow artists. Although this search for self is earnestly undertaken by the semi-autobiographical, sad protagonists of both novels, there’s a hypocrisy in it too and this is perhaps the point of the books. Margaret and Sheila are certain of their uncertainty, which indicates some level of self-trust. They do not extend this self-trust to any other part of their lives. In this way, they can outsource the responsibility of their identity to other people. If other people lead them astray on how to be and who they are, other people are to blame.

Later in the novel, Sheila says, “I know that character exists from the outside alone. I know that inside the body there’s just temperature.” Sheila believes the search for self takes place externally, by crowdsourcing information from art and acquaintances, and she is not wrong. However, the search for self cannot be successful if it takes place from the outside alone. In the last chapter of The Company She Keeps entitled “Ghostly Father, I Confess,” Margaret thinks to herself, “Now for the first time she saw her own extremity, saw that it was some failure in self-love that obliged her to snatch blindly at the love of others, hoping to love herself through them, borrowing their feelings, as the moon borrowed light. She herself was a dead planet.”

Borrowed feelings, borrowed identities, are not sustainable because they arise from a lack of self-acceptance and self-affection. One can not define themselves by others alone. One must be willing to sort through one’s internal thoughts, feelings, reflexes, compulsions and learn about themselves this way as well.

Both of these books about not knowing how to be could be labeled as autofiction. Autofiction is about the real-world self, unobscured by too much imagination or metaphor. You have to know who you are to write it in some way, to not design an allegory in demonstration of some neater point. McCarthy was famous for rendering scathing portrayals out of her fellow New York intellectuals, including her second husband Edmund Wilson in “A Charmed Life” and her mentor Philip Rahv in “The Oasis.” But McCarthy also gives herself the same treatment in these works. In The Company She Keeps, Margaret is appearance-obsessed, needy, cruel, indecisive, deeply self-aggrandizing, and deeply self-loathing. The point of her writing seems to be turning an unflinchingly perceptive eye onto everything around her. If it falls on you or me or her, too bad. She will not be reserved or choosy with her judgement or else she will be dishonest.

But McCarthy was not always praised for her will to write about herself so intimately. Although her New York Times obituary begins with the high opinions her contemporaries held of her (Elizabeth Hardwick says she had “will power, confidence and a subversive soul sustained by exceptional energy.” Norman Mailer calls her “our First Lady of Letters''), they are followed by a rather biting line that reads “The most tireless mythologizer of her life, however, remained Miss McCarthy herself.” While I believe McCarthy would have loved this sentence, there is an implied narcissism to McCarthy’s memoirs and fictions that I bristle against. Does writing about oneself really make one a self-mythologizer, an egoist? And if it does, is this necessarily a bad thing? I don’t think so, but Heti garnered similar criticisms for How Should A Person Be? In James Wood’s New Yorker review, he writes that the characters “are writers, artists, intellectuals, talkers, and they sit around discussing how best to be. This sounds hideously narcissistic. It is. Who cares about a bunch of more or less privileged North American artists, at leisure to examine their creative ambitions and anxieties?” Although he goes on to say that this is an “allowable indulgence,” the novel’s narcissism is presented as unquestionable fact and obstacle.

It seems like this is a response women writers receive, and if McCarthy is any indication, have long received to work resembling autofiction. Rachel Cusk was called a “peerless narcissist” in the Sunday Times and Marguerite Duras’s work was labeled as “nearly appalling in its narcissism,” if “also breathtaking” in the LA Review of Books. When men write auto-fiction, they don’t get nearly as many of these moral charges presented as criticism. Though Michel Houellebecq is a character in The Map and the Territory and most of his work is extremely self-contained and self-focused, he is not criticized or dismissed for his narcissism. His narcissism is instead treated as a foregone conclusion, a prerequisite to making great, exigent art. If he is controversial, it is because of other accusations: his islamophobia, his misogyny, his homophobia.

In order to write about oneself, one has to be interested in oneself. I push against the idea that self-interest is inherently narcissistic because self-interest is often the quickest path to self-awareness. But even if it is, why is it a criteria with which to qualify or dismiss writing? Why do we need our writers, particularly our women writers, to be paragons of selflessness, smiling demurely away everytime the subject of themselves is broached? All art is self-exploration, even art that professes to look outward. In order to write anything, one has to have examined their thoughts and feelings to understand what is true enough to make it to the page. To pretend that some art is more narcissistic than other art seems like splitting hairs. All art is narcissistic, even when it focuses on other people, even when it brings beauty into the world, even when it helps someone. There is nothing wrong with that.

Towards the end of The Company She Keeps, Margaret recounts the story of meeting a Russian refugee at a party. “They were asking him about his escape from the Soviets, and he had reached the point in his story where he saw his brother shot by the Bolsheviks. Here, at the most harrowing moment of his narrative, he faltered, broke off, and finally smiled, an apologetic, self-depreciatory smile which declared, ‘I know that this is one of the cliches of Russians in exile. They have all seen their brothers or sisters shot before their eyes. Excuse me, please, for having had such a commonplace and at the same time such an unlikely experience.’”

Margaret projects this sentiment onto the man, that he is in some way sorry for the story of his life being both excruciating and banal. It’s an unfair projection, but it serves to demonstrate something about Margaret and perhaps McCarthy as well. There is shame in writers, particularly women writers, sharing their life so plainly, so excessively. Yet often, the story in all its detailed ubiquity needs to be told. As McCarthy goes on to say, we cannot treat our “life-history as though it were an inferior novel and dismiss it with a snubbing phrase. It had after all been like that.”

McCarthy and Heti both wrote beautiful books about not knowing themselves. Books don’t function only as objects of self-exploration for their readers, but for their authors too. The process of writing requires that the writer turn away from others, turn towards themself, and this is where self-revelation takes place. Sheila Heti makes this point in her book The Chairs Are Where the People Go (2011). She discusses being in an improv group saying, “...what took me a long time to figure out...is that the thing we were providing for our audience was not the really valuable part. The really valuable experience was the experience that the people in the group were having. The experience that I was providing the group was in fact the experience that I hoped we were providing the audience, but were not.”

Maybe the primary purpose of Heti’s and McCarthy’s work is to solve the problem of themselves. This is explicitly what Heti does in her later book, Motherhood (2018). Through the actual writing of the novel, Heti answers the question of whether or not she wants to be a mother, deciding at one point, “This book is a prophylactic. This book is a boundary I'm erecting between myself and the reality of a child.”

And how can a book provide a journey for the reader if it doesn’t provide a journey for the writer? When a novel serves as a point of self-discovery for its author, it more honestly serves as one for its audience. By going so deeply and sincerely into themselves, Heti and McCarthy give their reader a manual on how to do the same. Or in other words, how to be.